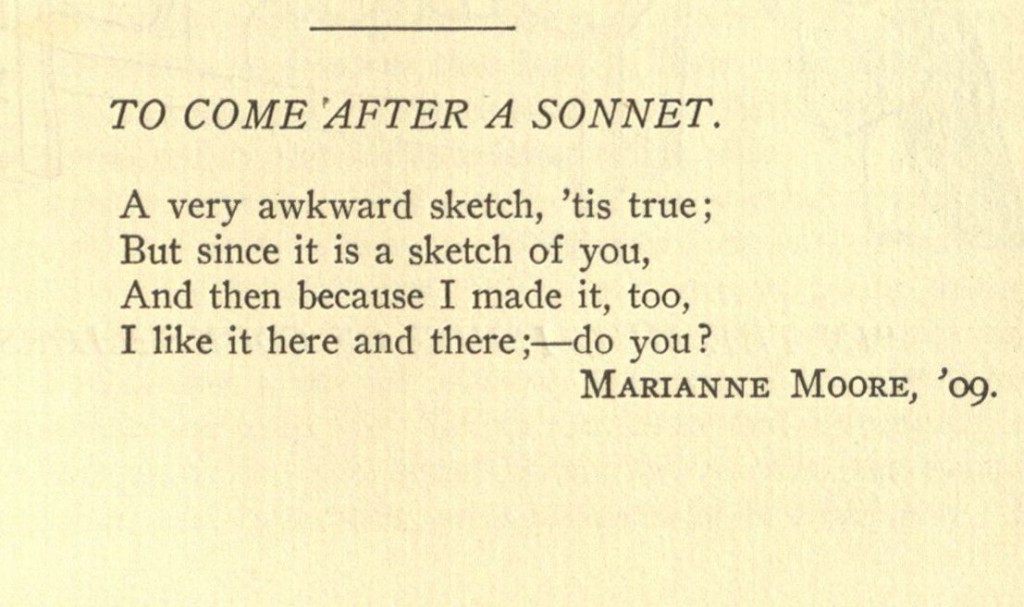

“To Come After a Sonnet”

A very awkward sketch, ’tis true:

But since it is a sketch of you,

And because I made it, too

I like it here and there; –do you?

In the Introduction to The Penguin Book of the Sonnet, Phillis Levin expatiates on the form and tradition of the sonnet. By choosing to write a sonnet, Levin imagines a kind of contract between the artist and her medium, “As a highly focused form, the sonnet attracts contradictory artistic impulses; in choosing and succumbing to the form, the poet agrees to follow the rules of the sonnet, but that willing surrender releases creative energy” (xxxvii). The young poet, Marianne Moore, chooses to evoke this contract in one of her first poems for Bryn Mawr’s literary magazine but does not partake in it. Moore’s “To Come After a Sonnet” engages with canonical form of the sonnet without conforming her own art. “To Come After a Sonnet” demonstrates the poet’s thoughtful engagement with the creation of her own style as well as experimentation with the various techniques of prosody. By examining this poem more closely, we can see how it becomes a path to understanding the poet that emerged.

Moore’s poetry is often difficult to interpret, because like her nod to the sonnet tradition yet refusal of the form, she creates gaps where there should be bridges. Rather than leading her reader through a highly organized structure, Moore often lets her quotes hang freely so that the reader must discern the context. We are left as readers to provide the links of the piece, finding commonalities or ways to connect the poem. The more that Moore leaves disconnected, the more that the reader must become a member of new type of contract– one that involves poem, author, and reader. In “ The Art of Silence and the Forms of Women’s Poetry,” Hugh Kenner redefines Moore’s editing as a process to expand rather limit “to delete was for [Moore] a kind of creative act” (ctd. in Krammer 154). Later in career, Moore becomes known for her multiple copies of poems, often deleting much of the poem as she revises it. However, deletion must then encompass revision, substitution, and visual recognition. Kenner speaks to the thoughtfulness with which Moore “deleted.” Moore’s poems are filled with gaps by their ordering, their visual dimensionality, and their concepts. In leaving spaces for interpretation, the poems fashion a new type of readership. A readership that comes after traditional notions that the reader is not involved in the contract.

Through this exploration of “To Come After a Sonnet,” I aim to establish gaps, and then provide two opposed readings (READING A and READING B) to demonstrate the rich critical complexity they allow. To access these readings, click on the paragraphs which indicate there are comments. The two readings provide alternative interpretations of the gaps that I layout. The gaps are not merely spaces which are visual blanks on a page. Gaps create a cessation in thought, in visual lineation and in narrative succession. I find this especially true when reading Moore’s early poetry. Reader-response theorist, Wolfgang Iser ,defines gaps by explaining that they occur, “… whenever the flow is interrupted and we are led off in unexpected directions, the opportunity is given to bring us into play our own faculty for establishing connection—for filling in the gaps left by the text itself”(“Reception Theory” 299). The gaps in this particular poem by are both gaps that are left open as well as ones that Moore fills. By concluding the poem with an open- ended question, Moore breaks out of the room of the sonnet tradition and explicitly creates room for the reader. This question elicits a response, necessitating the reader’s active engagement with the poem. By reprieving the speaker of answering the question, Moore creates a gap of silence which she prompts the reader to fill.

We are aided by punctuation of the poem. The use of colon, semi-colon, and dashes coupled with the fact that the poem is a mere two sentences suggests that Moore’s use of punctuation visually constructs space. The last line of the poem, “I like it here and there; –do you?” uses both a semi-colon and a dash. The combination of such particular punctuation provides the essential reconstruction of the reader. The semi-colon completes the thought and connects the speaker to the reader, yet the dash indicates a space, pause, even gap before the question is posed. Through the allowance of space between the speaker and the reader, Moore theorizes about the reception of art and representation. By allowing space within the poem, she acknowledges that gaps of time and personal interpretation are inherent in the process of reading. The idea that Moore potentially creates and fills her own gaps through punctuation is crucial to the argument of each reading.

However, even with the concrete markers of punctuation, we are lead into a more abstract gap– questioning the temporal relation of art to its own traditions. She creates an epilogue to a poem that the reader has no prior knowledge of or access to. This concept creates a mystery for the reader and leaves him or her questioning what the sonnet prior to this poem contained. The title of the poem alludes to this evasive sonnet, but it is uncertain whether there actually is a particular sonnet Moore had in mind or if the poem made to stand as a universal commentary to the traditional love sonnet. We, as readers, are left to provide our own context–one that comes “after” the idea of the sonnet. To fashion this context we must think about how we classify art: is it enough that a poem be a “sketch” (line 1) or must the author strive to make it something more? As readers, asked directly by Moore to fashion our own notion of a poem. By providing our answer, we engage in the dialogue. We complete the “sketch” so that it is only by our participation that poem is completed.

READING A:

In an interview for The Paris Review, when Marianne Moore was asked if she ever wrote when she received requests, her reply was, “… in college, I had a sonnet as an assignment. The epitome of weakness” (Interview 17-18). Whether Moore was referring to the assignment of the sonnet or the sonnet itself, Moore sustained her dislike of the forced poetic tradition; an opinion that can be traced back to an undergraduate student when she wrote “To Come After a Sonnet.” At Bryn Mawr College, Moore was surrounded by and unable to escape tradition. Through this poem, we learn to participate in the negotiation of tradition.

READING A:

Moore certainly had to have contemplated the tradition of the sonnet. Despite her efforts to separate herself from this tradition, “To Come After a Sonnet” lends itself to the traditional sentimental tone of English sonnet by sustaining the address of the beloved. Though Moore attempts to distance herself from tradition and community, she often evokes her dependence on them which exposes her inherent ties. For example, if Moore wanted to disassociate herself from the sonnet, then she should not have named it in the title. By doing so, rather than distancing the poem from the tradition she puts them in conversation with one another and sets the poem up for comparison.

READING A:

The word “After”, implies that Moore extends her poetry past the sonnet. However, by even mentioning the sonnet form, Moore draws on tradition and cannot escape the poem being compared to it. The result for the reader is not that Moore fashions her expression as innovative, but rather her poem falls short. Rather than express her critique of the sonnet, Moore’s poem of only one rhyme scheme “A A A A” attracts attention to what, when compared with the intricate rhyme of the sonnet, seems simple. The inclusion of the reference to the form also insinuates that Moore’s poem cannot stand alone; that for the meaning of Moore’ s poem to be evident, the reader must think about the sonnet. Even if Moore’s poem strains to cut ties with poetic tradition, it fails even before the actual begins, because of the reference in the title. Moore’s attempt to separate herself both in her craft and from her community is unsuccessful.

READING B:

The form Moore creates supports a more satirical reading. What is considered a free verse poem, “To Come After a Sonnet” instigates a dialogue with the form of the Sonnet by borrowing certain elements. For example, both the Petrachan and Shakespearean forms of the sonnet adhere to very distinctive rhyme schemes that can seem repetitive. The rhyme scheme employed by Moore’s poem is A A A A. While this could be attributed to a lack of imagination, it is the contrary. By using a single-rhyme rhyme scheme, the poem calls attention to the consistency of the sonnet. In “The Art of Silence and the Forms of Women’s Poetry,” Jeanne Kammer traces this move to several women poets,

Moore is not demonstrating her ability to rhyme; she uses rhyme to create a tension within in the poem. The scheme places emphasis on the end words; the words “true (line 1), “you” (line 2), “too” (line 3), and “you” (line 4) could be said to be making the argument that rhyme, as poetic device is outdated or too forced. However, considering that Moore goes on in her career as a poet to use rhyme creatively, it does not stand to reason that this is the case. Rather, it seems that by using these particular words, especially the repetition of “you” Moore is breaking the static addressee and fashioning a dialogue.

READING B:

The speaker acknowledges that the traditional sonnet form is not conducive to a relationship. In the form of the sonnet, the beloved is transformed from person into a one-dimensional muse, a projection of the speaker’s desire. However, through her dialogic form, Moore attempts to revert the transformation creating a structure that mimics in form the cooperative nature of a relationship.

Moore pushes the issue of form even further by creating a syllabic pattern that including the title is 7 8 8 7 8; whether or not the pattern was purposefully constructed, it is certain that Moore has an ear for syllabics,– the form which she pioneers in her later years. The combination of more colloquial language such as “sketch” (lines 1 and 2) antiquated language with “ ‘tis” (line 1) suggests a more mocking tone. The incompatibility of the speech highlights the issue certain elements of poetry becoming fixed; if poets cannot continue to retain the poetic tradition and refuse to compromise, like a stubborn suitor, then poetry will seem contrived and outdated.

READING B: “To Come After a Sonnet” is a poem that is easily dismissed as juvenile or without critical depth. However, it is steeped in the poetic female tradition that raises anarchy through format, punctuation, and diction.

READING B:

The use of space is important to consider while examining Moore from a feminist tradition. Gaps in structure are seen as feminine, because they are analogous to passivity. However, in her book H.D. and Sapphic Modernism, Diana Collecott theorizes this lack of cohesiveness in the poems of women Modernists is a way to mediate gender with the poetic tradition. Collecott draws attention to the fact that women poets often seem to value blank space as a representative piece of their art rather than an unfilled space. In “To Come After a Sonnet,” this certainly seems true. By ending the poem with a question for the reader, the blank space of the page becomes an invitation for a response.

Jeanne Krammer provides a provocative way to think about this blank space, “for women, there appears more often a determination to enter that darkness, to use it, to illuminate it with the individual human presence” (158). This poem by Moore is an excellent example of how to illuminate a space with “human presence.” Rather than turn the page after completing the poem, the reader is forced to take action, form an opinion, and answer the speaker. Moore creates a three-dimensional portrait of her muse. She acknowledges that silence is crucial, because it provides the possibility of a voice not yet heard. Moore not only enters the “darkness” of a space that steps purposely aside from tradition but takes the reader with her.

This dynamic that Moore creates transforms what is a simple poem into an intricate one worth considering. She raises many questions and breaks traditional rules not only through her use of words but through her intrepidness, acknowledging that we must enter into a space not yet marked.

READING A: This poem affords the reader an intimate view of some of the issues that Moore struggles with throughout her career; only here it is a rare opportunity to see some of the cracks in her armor and to experience the vulnerability inside.

READING A:

The publication of the poem in the Bryn Mawr literary magazine, The Tipyn O’ Bob ensures the attachment to community. The creation of the other in the dialogue cannot be realized unless there is someone reading the poem—that reader would be a Bryn Mawr student. Moore had to acknowledge this with her choice to publish her poem in the campus literary magazine. Without a community of readers, her poems would not have survived. Even if this poem was meant to deny the influence of the female community or poetic tradition, the virtue of the publication negates any claim the poem itself is making. This debacle plagued Moore throughout her career. Moore attempted to become a poet without conventionally publishing a collection of her poetry, but instead publishing poem by poem as she chose. However, the move that both undermined her independent sense of artistry but also assured her success was the publication of her first book by former Bryn Mawr classmate and fellow poet Hilda Doolittle and Bryher. (Schulze 45) This poem affords the reader an intimate view of some of the issues that Moore struggles with throughout her career; only here it is a rare opportunity to see some of the cracks in her armor and to experience the vulnerability inside.

The element in her poem that best demonstrates the inability to break away is the punctuation. There is not a period in the whole poem; the closest Moore comes is a semi-colon. This semi-colon is at the center of the poem. It unravels all the work that Moore does constructing a dialogue. By asking a question and breaking the frame, Moore establishes two perspectives and acknowledges the individuality of the muse. However, rather than separating these two opinions and full distinguishing their identities, the semi-colon still joins them in a way that is artificial. The presence of the semi-colon represents the larger, more looming presence of community. There can be no voice distinguished as unique or individual if is not set against that of the community. The connection between artist and muse, as well as Moore’s inability to fully distance the two, makes the larger claim that the artist is never fully objective and cannot be removed entirely from the poem. Moore is known to be struggling with this concept as she writes to Marcet Haldeman, and copies “To Come After a Sonnet , then adds “To M.B.M. of course, it was in the old days” (Moore). Moore then crossed out the bit about the dedication. In doing so, she reveals her own struggle with intersection of poetry and the personal. Though she crosses out the sentiment, like the semi-colon, it is not fully erased. Thus, the remnant provides enough to expose her.

READING B:

In the sonnet tradition, women are often objectified into one-dimensional muses. This is especially true when thinking about the Dante and Petrach and their influence on how the speaker relates to his female subject. The female subject becomes glorified, even sanctified as an art. Moore breaks this tradition acknowledging that the subject too has an opinion. The last line of the poem, in fact the last two words, transform the subject from art into person and even more importantly, an independent person with her own perspective of the art; the woman becomes a participant rather than a captive bystander. Examining the syntax of the poem, the whole poem is a single sentence through the point of view of the speaker until the last line. The semi-colon connects the only two sentences of the poem. This is particularly interesting, because Moore could have chosen create two separate sentences; it is the fact that she chose to link them makes a subtle, but larger claim about the dependency of the artist and the subject. Comparing the volume in which the artist self-reflects to the acknowledgement of the subject’s voice, one assumes that the artist dominates as he has in the past. However, the presence of the semi-colon allows for the idea to move in a different direction, one that establishes a more co-dependent partnership rather than a symbiotic one. In doing so, Moore suggests a more dialogic relationship in art. The structure of the poem allows for it to be a critique that this reciprocality does not occur enough in the art itself but is often an afterthought of the process. Thus, this poem not only comments on the older art form, it suggests a new one.

READING B:

While Moore creates a radically different addressee, she also provides an alternate portrait of the poet. As readers, we are privy to the pressures that plague a self-conscious artist. Moore is not associated with confessional poetry, but the way in which this poem fuses irony as well still reveals some truths gives a more personal tone. A letter in Special Collections reveals that Moore struggled with her romantic attachment to the poem. As she writes to Marcet Haldeman, Moore copies her new poem and adds “To M.B.M. of course, it was in the old days” (Moore). Moore then crossed out the bit about the dedication. In doing so, she reveals her own struggle with intersection of poetry and the personal. The fact that she chooses to strike out the sentence demonstrates her desire to keep the connection distant. By demonstrating this desire, Moore fashions a contract with herself as art. Rather than merely recording her sentiments on the page, she endeavors to create for art’s sake and for a greater purpose in society. Though there may be evidence of this struggle in a letter, Moore did not include any dedication or mention of M.B.M. in the publication. With the elimination of this sentiment, Moore demonstrates her desire to be seen as a serious artist with a distance from her work and more intentions for her art than personal motives.