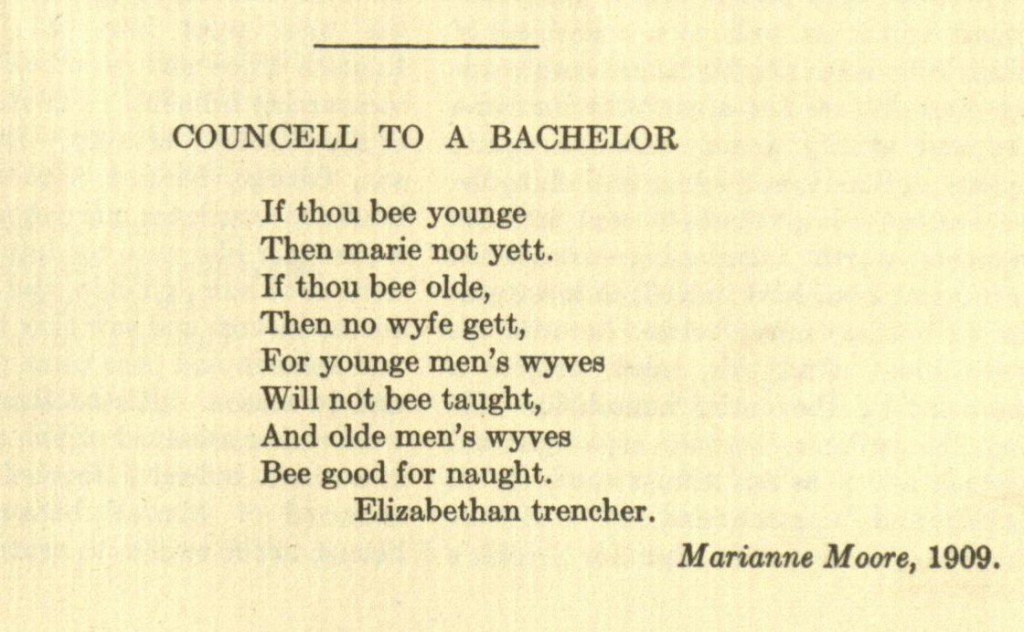

“Councell to A Bachelor”

If thou bee younge

Then marie not yett .

If thou bee olde,

Then no wyfe gett,

For young men’s wyves

Will not bee taught,

And olde men’s wyves

Bee good for naught.

–Elizabethan trencher, Bodleian Library

In her poem, “Councell to A Bachelor” Marianne Moore engages with an act of intellectual appropriation through physical space. Moore crafts the poem from a motto on a trencher, most often defined as a piece of dinnerware that has a motto inscribed on it. In “Councell to A Bachelor, ” however the page is substituted for physical object. In doing so, the question becomes does the page serve an alternate purpose than merely being functional. “Councell to A Bachelor,” interrogates our use (or perhaps more correctly misuse) of the page as an element of the text. Can the page be as evocative as text? The poem asks us to think about what it means to separate the motto from the physical artifact and repurposes it. Moore challenges us as readers to think about how context interacts with the text itself to produce meaning.

Originally the “Councell to A Bachelor” appears in The Lantern, the Bryn Mawr Alumnae Magazine and was then published two years after in Poetry Magazine, a national publication (Schulze 150). In Becoming Marianne Moore, Robin Schulze emphasizes Moore’s insistence that the motto be printed with its source of a trencher from the Bodleian Library, because of “her lifelong desire to give credit for words not strictly her own” (150). Schulze interprets Moore’s insistence of citation as demonstrative of Moore’s cautiousness to claim to author writing she did not. However, if this is the case, why did Moore not carefully annotate every poem she wrote?

Moore’s later poem “Marriage” provides a good juxtaposition to explore her use of citation as well as demonstrates her continued interest in the subject of marriage and its relation to authority. “Marriage” is sundry mix of phrases, or to reference Moore’s own definition of her poems– a “compilation of anthologies,” that she read and overheard on the subject (“A Burning Desire to Be Explicit” 5-6). By noting that Moore thought of her own work as an “anthology,” it is apparent that she considered about what it meant to collect pieces and arrange them. The word “anthology” comes from Greek meaning “to gather, or a collection” (“Anthology” def 1a). Moore creates her poems like a curator. She collects phrases to put them in dialogue with each other as well as with the environment of text. In return, the pages becomes more than a flattened, two-dimensional work. The features of text are not segregated –text and page– but rather they interact with each other. These interactions create an opening for an intra-textual argument that Moore utilizes. Critics often note how a lack of text can create the effect of silence. For example, in her book, H.D. and Sapphic Modernism, Diana Collecott discusses how silence in poetry becomes powerful for women poets. She cites Moore’s comment in H.D.’s obituary that H.D. “magnetize[s] the reader by what is not said” (148). Moore moves beyond how words relate to the space on the space and the page to the context which it is place demonstrates a silence the reverberates in all aspects of the the work. The poem “Councell to a Bachelor,” especially, recognizes how elements, which seem inconsequential or silent function to subvert the text.

Scholars have been tracing the sources of “Marriage” and are still unsure that all allusions and phrases are accounted for. In fact, there is still no comprehensive collection of Moore’s poetry that has compiled a full annotation of her sources. Moore is renown for incorporating a multitude of sources into her poems–playing with textual boundary and context. These poems at Bryn Mawr, particularly “Councell to A Bachelor” marks the beginning of Moore’s intentional investigation of textual agency.

While Moore may have been referencing her sources in “Councell to A Bachelor,” and taking in to consideration “Marriage,” I do not think her references sole purpose were to assuage her fear of intellectual piracy. Moore’s insistence on demarcation between her work and the original motto creates the tension which provides the theoretical complexity. On first read, this poem seems nothing more than replication of the motto carved on an Elizabethan trencher. It could be easily mistaken without a note that Moore added a title to specify and a second line to complete the first quatrain. The conceit of the poem perpetuates patriarchal dominance by what would be standard advice to a male in Elizabethan culture. As the reader, we are positioned as a male reader receiving advice on how to choose a wife. This poem could fail to be fruitful to us as readers if the only contention of the poem was to re-experience the motto in a different time. But Moore uses citation to create a disruption of context. As readers, we depend on context to orient us to the reading. Moore disorients us from this reliance. The intrigue, then, does not stem from the content of the message, but rather from the idea that Moore is introducing this archaic conceit into the specific context of an all-women’s college and later of a literary magazine. As readers, we are not puzzled by metaphor, awed by maneuvers of clever rhyme, or even asked to tease out the meaning. Even as an undergraduate Moore studied and wrote poetry with dexterity; based on her exposure to poetry, it seems unlikely that she considered this poem’s content to carry the meaning of the poem.

We need to interrogate the physical spaces that the poem engages with and how these places make claims on academia. First, let us consider the Bodleian Library where Moore claims the trencher was found. In Schulze’s footnote to the poem Moore assures the editor of Poetry that the motto inscribed on the trencher has never been published, and I have not been able to trace any remainder of the original. It is unclear as to how Moore obtained the poem. It is possible that M. Carey Thomas brought it her students’ attention, because Thomas travelled overseas often. I do not doubt the authenticity of Moore’s source, and further I do not think that verifiability of her actual retrieval of the motto affects the reading of the poem. In fact, the uncertainty surrounding the acquisition of the motto insists that we as readers reflect on our relation to context and consider what role it plays in our reading. To what extent must art be factual? In both the reception of the motto as well as the multiple publications, ambiguity clouds the context. Moore’s equivocation is purposeful not mistaken. Through this cloud of confusion, we must consider each option and open our readings to include not only the text that is obvious, but the interpretative elements that often escape our purview.

The question may also arise: with such small emendations by Moore’s own hand, can we suggest that this is her poem? Part of this question is answered by Moore herself overtly and part leaves a gap for the reader to fill. The fact that Moore chooses to republish this poem later as an established poet indicates that she felt it was worthy of consideration. The gap that she has left for us to ascertain is two-fold: why does she think so and do we agree? In an attempt to answer at least the first question, what makes this poem more than simply a reproduction, it is necessary to return to the time of its original publication Moore’s study as an undergraduate at Bryn Mawr College.

The citation of the library as the original source and Moore’s acknowledgement of her revision and republication allow the poem to set two institutions (Oxford and Bryn Mawr and with the later publication, academia and intellectual publication) in conversation. The Bodleian Libraries are affiliated with Oxford University. As a result, the Library has a prestigious intellectual reputation as well as some of the most comprehensive holdings in the world. By evoking the space of the Oxford library, Moore also implicates the university itself. Oxford represented the pinnacle of intellectual rigor and success. Moore uses the motto as a metonymy for institutional sexism, a crusade mostly attributed to Virginia Woolf in the opening of her essay A Room of One’s Own as she attempts to enter the fictional Oxbridge:

“I must have opened it, for instantly there issued, like a guardian angel barring the way with a flutter of black gown instead of white wings, a deprecating, silvery, kindly gentleman, who regretted in a low voice as he waved me back that ladies are only admitted to the library if accompanied by a Fellow of the College or furnished with a letter of introduction” (Woolf 5-6).

Through the physicality of the trencher as well as the intended audience of the motto, Moore also is denied entrance. The essence of the trencher does not focus on the scholarly but rather on a much different type of knowledge-one of what seems to be common advice. The trencher comprises as Moore’s title suggests advise to young eligible men. The trencher and the library both comprise of modes of knowledge which limit access and advice to women. Women were denied an Oxford education until 1920. We can imagine that the motto was inscribed on a bowl that was part of the dinnerware which was used for communal meals at one of the Oxford colleges. Young male scholars would have had to pass the trencher onto one another perpetuating the cycle of exclusion literally and metaphorically.

But Moore interrupts the cycle by commandeering this passage and redefining it. She compresses and expands space or perhaps most importantly, she subverts it for her own purposes. The lines that Moore adds to the poem may not seem rebellious or controversial. In fact, without Moore’s specific citation, it may be impossible to tell that any lines were added at all. However, our attention is purposely brought to the citations, not to acknowledge the work that is not Moore’s but rather to think about her additions to the motto. By being told that Moore added to this motto, we understand that there is a textual a coup d’état occurring in the poem. Moore’s title and lines encroach upon a territory which does not welcome her. One of the two variations that Moore includes in the poem is the title. Of all of the variations that Moore could have chosen to make, the action of adding a title corrupts the intention of the poem and reasserts it. By naming the motto, Moore takes the authority that has been denied her and by doing so, she reclaims it and redefines it. Before this can happen though, Moore destabilizes the authority of the poem which relies heavily on the patriarchal tradition which allows it to continue. By taking the poem out of the library, Moore breaks the sacrosanct boundaries of context. By publishing the revised motto as a poem, she physically breaks the cycle allowing the reader to receive the trencher without kindly gentlemen turning them away; the reader must simply turn to the page. The acts of publication then are the means of poetry.

Moore publishes “Councell to A Bachelor” twice– first in Bryn Mawr’s alumnae literary magazine The Lantern and second publication in the magazine Poetry. Unlike in many of her republications, variation do not appear in the text of the poem itself. However, as I suggested earlier ( in paragraph 15) the poem’s major interpretive work depends on the relation of text to context. Both titles of the journals lay a suggestive framework in which the poem becomes revised.The first publication in The Lantern, pushes the boundaries of access. The second publication in Poetry magazine suggests with its title that its contents are are defined as poetry. Moore challenges that assertion by publishing a motto she only slightly modified. Below this paragraph are two links: The Lantern Publication and Poetry Publication. I have provided more in-depth analysis of each new context of publication and how we might consider it as a revision. Each link will pop-up a window which allows the reader at most to have different three windows. By allowing each publication its own window, I have attempted to represent the differences in physical and intellectual space.